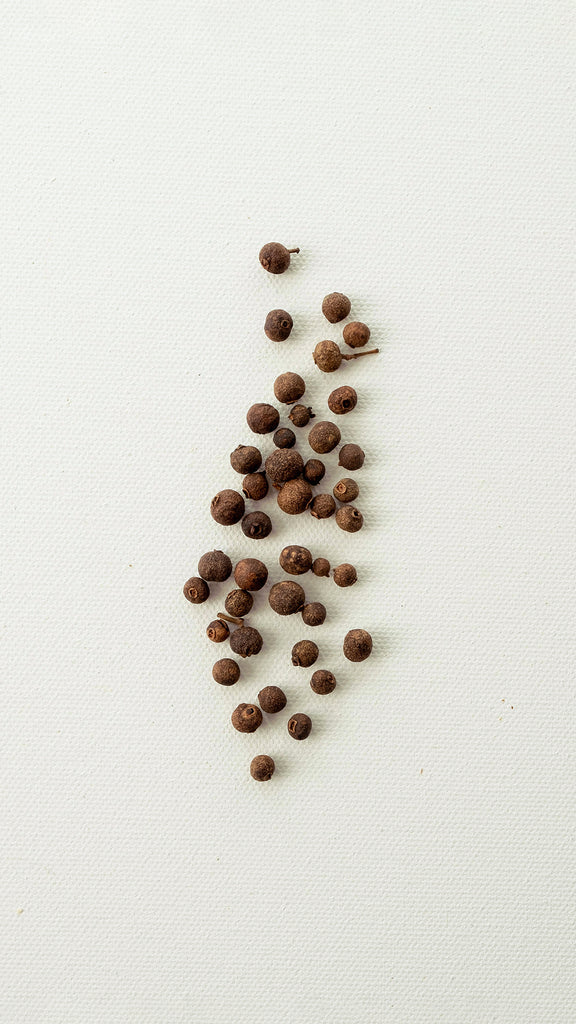

Allspice (Pimenta dioica) is a dried unripe berry in the Myrtaceae family native to the Greater Antilles, southern Mexico, and Central America. A common warming spice, allspice has a comforting, autumnal aroma that comes from the antibacterial compound eugenol.

Now commonly cultivated in warm climates, allspice first became popular in the early 17th century because of its distinct flavor and aroma. The English named the botanical ‘allspice’ because it combined the sweet, warm flavors of cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove into one ingredient. While the botanical offers its own unique flavor properties, it is still often included in ingredients lists with those other warming spices to balance and bind them together.

The dried fruit of the Pimenta dioica plant, allspice is picked when green and unripe and left out to dry under the hot summer sun. These fruits are left until they’re small and shrivelled, resembling peppercorns. In many parts of the world, allspice is called ‘pimento’ because the Spanish once mistook the botanical for black pepper, which is called pimienta.

The allspice we know and love, though, is actually just one part of the Pimenta dioica plant. The Pimenta dioica plant’s leaves are harvested to be used in a similar capacity to bay leaves. In regions where allspice is a local crop, the wood of the Pimenta dioica is also used for smoking meats.

Native to Jamaica, allspice is an important ingredient in Jamaican cuisine like jerk seasoning, with its wood being used to smoke jerk. The spice makes its way into other cuisines as well, featuring prominently in Mexican cooking and in “pimento dram,” an allspice liqueur produced in the West Indies. In the Levant, allspice is used to flavor stews, tomato sauces, and meat dishes, while in northern Europe, it’s often found in sausage, curry powders, and in pickling.

In the US, allspice is reserved mostly for desserts and drinks, from pumpkin pie to mulled wine. Its sweet, dry aroma lends itself nicely to woodsy, comforting fragrances like Four Thieves, where it joins allspice and clove for a warm scent to balance the soothing herbal qualities of eucalyptus.

Angelica (Angelica archangelica) is a biennial herb belonging to the Apiaceae family believed to be native to Syria. The “Root of the Holy Ghost,” as it is sometimes called, is now a common flavoring agent in gin, aquavit, and various liqueurs, as it lends the liquids an earthy, herbal quality.

Native to temperate and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere, angelica is a bit of a nomad. These days, the plant is grown widely throughout Syria, France, Germany, Romania, and some East Asian countries, among others. One of the few aromatic plants that thrives in cold climates, angelica was long considered a life-saving food, often staving off starvation when other nutrients were unavailable. One species of the botanical–Seacoast angelica–was eaten as a wild substitute to celery, while in the 1700s the roots and stems of angelica were candied and enjoyed as sweet treats in England.

The plant’s musk-like aroma has made it well-suited for perfumery, and it is still found today in musky fragrances like Jo Malone’s Tuberose Angelica Cologne Intense. Outside of its culinary and olfactory uses, angelica was used by the Sami people of Lapland in the production of the fadno, a traditional reed instrument akin to a flute. In fact, the instrument derives its name from the botanical, as fadno literally means one-year-old angelica.

Angelica is named after the legend of an angel who appeared to a monk in a dream and told him that the plant could cure the plague. A derivative of the Latin word angelicus meaning angelic, angelica was long held up as a cure-all across cultures. The Missouri tribe of North America smoked the plant to treat colds and respiratory ailments, while the boiled roots were applied to wounds by the Aleut people to speed healing. Today, essential angelica oil is used widely as a rub for joint pain. The botanical is also prized by Wiccans, who use the herb to dispel negative energies and promote healing.

There are over 40 known species of angelica, with some grown to be used as flavoring agents and others for medicinal purposes. Only very advanced plants are perennial, with most dying after seeding just once. The botanical grows abundantly in parks and squares throughout London, although its perception varies. Some view it as a useful form of foliage, while to others it’s treated as more of a bothersome weed. The plant continues to be valued for its taste, and is used as a flavoring agent in Aquavit and various liqueurs, including Chartreuse, Fernet, and some vermouths. Angelica is one of the most important botanicals in gin distillation, falling third only to juniper and coriander. Its roots are most commonly used in gin, although some brands also use the flower and seeds. When distilled, the botanical adds an earthy, bitter, and herbal quality to the spirit.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) is a plant in the Solanaceae or nightshade family native to the drier areas of India. Classified as both an adaptogen and a nootropic, the bitter botanical can help the body manage and cope with stress while improving memory and concentration.

Ashwagandha goes by a few different names, including Indian ginseng, poison gooseberry, and winter cherry. Though entirely unrelated to the plant, ashwagandha is often called Indian ginseng because it is treated similarly in Ayurveda–the Indian system of medicine–as ginseng is treated in traditional Chinese medicine. One of the most important herbs of Ayurveda, ashwagandha has been used for several millennia as a Rasayana or rejuvenator, an herbal remedy intended to promote longevity.

Though the effects of ashwagandha are impressive, you wouldn’t guess it based on appearance alone. The unassuming plant stands at just one to two feet tall, with dull green leaves bearing small orange fruit. It is primarily cultivated in the drier regions of India, but can also be found in Nepal, China, and Yemen, where it thrives in dry stony soil and direct sunlight.

The species name somnifera means sleep-inducing in Latin, referring to the calming properties of the plant. Ashwagandha, meanwhile, comes from a combination of the Sanskrit words ashva, meaning horse, and gandha, meaning smell. Its loose translation is “the smell and strength of a horse.” While the smell is rather literal, the strength winkingly refers to the plant’s aphrodisiac qualities, as it is sometimes used as sexual function support. ‘

Legend has it that Apollo found the ashwagandha plant and gave it to his son Asclepius, a celebrated hero of health and wellness in Greek mythology, cementing the botanical early on as an important healing herb. It’s purported that Alexander the Great and his army would prepare wine made with ashwagandha to give them the energy and vigor needed to succeed in battle.

Today, ashwagandha is classified as both an adaptogen and a nootropic, words usually reserved for the wellness tea and tincture space and found far less frequently in gin and other spirits. To put it simply, an adaptogen is a plant that helps the body adapt to and cope with stress. Nootropics, meanwhile, are thought to enhance cognitive function, improving memory, creativity, concentration, and even motivation. You’ll rarely find ashwagandha for purchase in its whole form, as the botanical is almost always produced, packaged, and sold as a powder or pill. When distilled, the botanical offers a bitter, herbal taste that acts as pleasant foil for brighter citrus notes and earthy mushrooms.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Basil (Ocimum basilicum) is a culinary herb in the Lamiaceae family native to tropical regions from central Africa to Southeast Asia. There are many varieties of basil, though Genovese and Thai basil are the most common.

Basil is delicious. Ground up into pesto or sprinkled onto larb, the anise-like herb lends freshness and sweetness to countless dishes across continents and cultures. Thai and Genovese basil are the most popular varieties, but holy basil and lemon basil are plant powerhouses in their own right. Holy basil, also known as tulsi, is a powerful healing herb in Ayurveda and is highly revered in Hinduism, while lemon basil offers a citrusy flavor perfect for lightening up your favorite basil-centric dish.

In Greek mythology, basil was thought to be an antidote to the basilisk’s fatal stare and breath. Some say that’s where it got its name basilicum, while others believe the name comes from the Latin word basilius, meaning “royal plant,” because of the botanical’s usage in the production of royal perfumes.

Basil’s symbolic significance doesn’t end there; in ancient Greece, the plant represented hatred, while in Portugal dwarf bush basil was presented alongside a poem and a paper carnation as a profession of love on the religious holidays of Saint John and Saint Anthony. Jewish folklore suggests the plant adds strength while fasting, and in the Greek Orthodox Church, basil is used to sprinkle holy water. The plant has long been used in burial rites, as well, placed in the mouth or the hands of the dying to ensure a safe journey into the afterlife.

It’s a rich history, especially for a plant that we now know best for its appearance alongside pine nuts and parm. Basil’s modern day uses go beyond pesto, though. The botanical is increasingly used for its essential oils, which contain high concentrations of linalool, a soothing terpene found in lavender that works wonders in easing anxiety and stress. In Basilisk Breath, basil is complemented by herbaceous notes of peppermint, rosemary, sage, and thyme for a refreshing clean.

The black spruce (Picea mariana) is an evergreen coniferous tree in the Pinaceae family native to the northernmost parts of North America. It's used in everything from essential oils to fast-food chopsticks.

Venture up north to Canada and you’ll find the black spruce spanning across all 10 provinces. It’s the official tree of both Newfoundland and Labrador, where it outdoes every other tree by sheer number. You can find the black spruce stateside too, where it thrives in Alaska, the upper Northeast, and among the Great Lakes. It’s an integral part of the biome known as the boreal forest, or otherwise known as taiga.

The Latin epithet for the black spruce’s botanical name, mariana, means “of the Virgin Mary,” though it’s not entirely clear why it bears the name. What is clear, however, is the black spruce’s propensity to grow in harsh, wintery conditions.

The growth of a black spruce varies substantially depending on where it’s planted. In swamp conditions, the tree shows progressively slower growth rates. In the northernmost regions of the black spruce’s range, the trees are often seen with less foliage on the windward side. Called “drunken trees,” these tilted trees are associated with thawing of permafrost.

While the black spruce has all the characteristics of a classic spruce, such as glaucous green needles and scaly bark, Its cones are by far the smallest of all the spruces. Often less than one inch long, these cones are nearly round, with a dark purple hue that ripens to a red-brown color when mature.

In Canada, the black spruce is the primary source of pulpwood, the material used to make paper products. The tree is also used to make beer and spruce gum, a chewing material made from the resin of spruce trees that has long been used medicinally to treat coughs and heal deep cuts.

Black spruce is one of several coniferous notes found in AMASS Forest Bath, which harkens back to the coastal forests of the Canadian Pacific Northwest.

Cacao (Theobroma cacao) is a small evergreen tree in the Malvaceae family native to the deeper tropical regions of Mesoamerica. Its seeds, known as cocoa beans, are used in the production of chocolate and cocoa butter. Unlike commercially produced chocolate, however, unprocessed cacao has a bitter, nutty taste and is loaded with powerful antioxidants.

While varieties of cacao abound, there are three primary types–Forastero, Criollo, and Trinitario. The first, Forastero, is the most widely used, making up 80 to 90 percent of the production of cocoa and chocolate. Terminology surrounding the plant and its products can get tricky, but this is the general breakdown: the term cacao typically refers to the plant or its beans before processing, while chocolate refers to anything made from the beans. The word cocoa, while sometimes used interchangeably with cacao, technically refers to the fine powder of roasted cacao beans after a portion of their fat has been removed. Cocoa butter, meanwhile, refers to that fat extracted from the cocoa bean.

Native to Mesmoamerica, for centuries cacao was considered valuable enough to use as currency. Prized for its powerful antioxidants and nutrients, cacao was believed by the Maya and Aztec peoples to possess magical properties suitable for use in the most sacred rituals of birth, marriage, and death. In fact, Aztec sacrifice victims who felt too melancholy to join in ritual dancing before their death were often given a gourd of chocolate tinged with the blood of previous victims to cheer them up.

According to Mayan mythology, the plumed serpent gave cacao to the Maya after humans were created from maize by the divine grandmother goddess Xmucane. The Maya celebrated an annual festival to honor their cacao god, Ek Chuah, an event that included the sacrifice of a dog with cacao-colored markings, additional animal sacrifices, offerings of cacao, feathers, and incense, and an exchange of gifts.

The earliest linguistic evidence of chocolate consumption stretches back three or even four millennia, to pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica such as the Olmec. Anthropologists from the University of Pennsylvania announced the discovery of cacao residue on pottery excavated in Honduras that could date back as far as 1400 B.C.E. Cacao is believed to have been fermented into an alcoholic beverage at the time, which was used as a ritual by men only, as it was believed to be intoxicating and therefore unsuitable for women and children.

Today, cacao nibs or powder are used in desserts, smoothies, granola, and more. Compared to chocolate, cacao is much more bitter and richer in flavor.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

The California Bay (Umbellularia californica) is a large hardwood tree in the Lauraceae family native to coastal forests of Northern California. Similar in flavor and usage to Turkish bay leaves, California bay leaves offer a subtle herbal flavor when distilled.

California bay trees typically grow in coastal forests of Northern California, stretching up as far north as Oregon and sometimes down into the dry desert heat of Southern California. Considered an excellent tonewood ideal for woodwind and acoustic instruments, the California bay is often sought after by luthiers and woodworkers.

Today, the wood from the California bay–otherwise known as Myrtlewood–is the only wood still used as a base for legal tender. The story goes that in 1933, the only bank in North Bend, Oregon was forced to close, leading to a city-wide cash-flow crisis. The crisis was resolved when North Bend decided to mint its own currency, using Myrtlewood coins printed on a newspaper press. The city promised to redeem the coins for cash once it became available, but many decided to hold onto their sheckles as collector’s items, which have since become incredibly valuable.

The California bay’s storied past doesn’t stop there: in 1869, the Golden Spike was hammered into a railroad tie made from California bay wood, signifying completion of the Transcontinental Railway, which linked the East Coast to the West by way of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads.

Despite its longstanding cultural significance, the California bay is now much more prized for its leaves, which have a flavor similar to but much more assertive than the subtly sweet Turkish bay leaves. Both leaves are added to soups, stews, and sauces to imbue a deep, complex flavor, and are removed before eating.

Medicinally, poultices of California bay leaves were once used to treat rheumatism, among other ailments; a poultice was placed on the heads of those who suffered from seizures, for example, to restore consciousness. Single leaves were inserted into the nostrils to cure headaches, while a tea was made from the bark and leaves to treat the common cold and clear mucus from the lungs. In some Native American tribes, California bay leaves were used as natural bug repellents.

Today the California bay grows widely throughout the coastal forests of Northern California and the Pacific Northwest. Despite its NorCal roots, the plant has found its way into AMASS Master Distiller Morgan McLachlan’s Los Angeles backyard, where it grows alongside rosemary and grapefruit.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) is a plant in the Zingiberaceae family native to tropical and subtropical Asia. The sweet warming spice comes in two varieties – black and green – and is used widely in Indian and Middle Eastern cuisine.

Cardamom comes from the Elettaria and Amomum plants, which grow in thick clumps of leafy shoots with dark green, sword-shaped leaves. On those leaves grow small pods, what we commonly know as cardamom. These thin papery shells encasing tiny black seeds are available in two varieties; black and green. In the fourth century BCE, Theophrastus, the Greek father of botany distinguished the two varieties of cardamom. While green cardamom, Elettaria, is more commonplace, the black variety, Amomum, has a smoky flavor well-suited for savory dishes.

A known breath freshener, cardamom is used by the Wrigley gum brand Eclipse “to neutralize the toughest breath odors.” Individual seeds are sometimes chewed in the same manner as chewing gum for this very reason. Before the advent of toothpaste, ancient Egyptians chewed on cardamom seeds as a way to keep their teeth clean and breath fresh.

Native to tropical and subtropical Asia, cardamom is now primarily cultivated in Guatemala, Malaysia, and Tanzania. There it is harvested in October, when its whole pods are laid out to dry in the sun or in curing houses. Guatemala is currently the largest producer of cardamom, and in some regions the spice is a more valuable crop than coffee. Green cardamom is one of the most expensive spices by weight, surpassed only by vanilla and saffron. Thankfully, its flavor is potent and very little is needed to imbue a sweet, spicy taste.

The spice is widely used in Indian and Middle Eastern cuisine, added to sips, sweets, and savory dishes alike. One of its applications is in gahwa, a coffee blend often recognized as a symbol of hospitality in Indian households, with some even considering it rude to refuse a cup. In recent years, cardamom has been increasingly used in gin distillation, becoming emblematic of the modern gin movement. Its complex warm flavor becomes subdued when distilled, lending a subtle sweet grassiness.

Found in: AMASS Dry GIn

The cedar leaf (Thuja Occidentalis) comes from the cedar tree, a genus of coniferous trees belonging to the Pinaceae family native to the western Himalayas and Mediterranean region. These leaves have a sharp, fresh, and woody camphor scent that is used often in pharmaceutical products for its therapeutic properties.

Because cedar trees share a very similar cone structure with firs, it was long thought that the two were genetically similar. Molecular evidence, however, shows that the genuses are actually quite different.

Cedar leaves are evergreen and needle-like, growing in an open spiral phyllotaxis on long shoots. They are arranged in dense spiral clusters of 15-45 needles together, and vary from a bright, grassy green to a deep verdant hue to a dull blue-green depending on the thickness of the layer of white wax that protects the leaves from desiccation, or drying.

The plant’s seeds have several resin blisters which possess unpleasant tasting resin. This resin is thought to be a deterrent to squirrels, who otherwise are considered predators due to their propensity to snack on the seeds.

The cedar genus contains four known species, including the Atlas cedar, the Cyprus cedar, the Himalayan cedar, and the Lebanese cedar. These species vary in size, color, and distribution, though all grow in mountainous regions around the world.

While cedar wood and cedar berries are more commonly used, cedar leaves have their own speciality uses. These leaves were long thought to be useful in steam baths, helpful in curing rheumatism, arthritis, and congestion, as well as to wash swollen feet and burns. It was used in treating scurvy as late as the 1900s, and today is commonly used in perfumes, cosmetics, and soaps for its delightful aromatic properties. A carrier oil is recommended when applied to the skin to dilute both the scent and effect.

In AMASS Forest Bath, cedar leaf oil blends with Siberian fir and black spruce for a full forest aroma that transports to the towering trees of the Pacific Northwest.

Cedarwood (Juniperus virginiana) comes from the red cedar, a species of juniper native to eastern North America from southeastern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico and east of the Great plains. Its warm and woodsy aroma makes it a commonly used oil in aromatherapy.

Cedarwood comes from a tree bearing many names; red cedar, Virginian juniper, pencil cedar, and aromatic cedar being just a few of them. It’s considered a pioneer species, meaning it’s one of the first trees to repopulate eroded or damaged land. Among other pioneer species, it lives unusually long, sometimes standing for over 900 years.

Because of its propensity to thrive on forgotten land, the red cedar is often found in prairies, old pastures, along highways, and near recent construction sites. Where there is nothing, the red cedar grows.

It’s for that reason the red cedar is considered an invasive species, growing sometimes in spite and regardless of whether it is wanted. It’s fire-intolerant, however, and in the past has been controlled by periodic wildfires. Its low-hanging branches provide a ladder that allows a flame to engulf the whole tree, and in places with dense red cedar populations, the tree is often to blame for the rapid spread of wildfires.

The red cedar’s fragrant, soft wood is surprisingly durable. Because of this, fence posts are sometimes made from its wood. Its strong aroma keeps away moths, which is why closets are often lined with cedar to keep away cashmere-loving pests. In the past, the heartwood of the tree was used for the production of pencils. Over time, however, the supply has diminished and the wood of the incense-cedar has largely replaced it.

Among many Native American cultures, burning cedarwood is believed to expel evil spirits prior to healing ceremonies. Several tribes have also historically used the wood to demarcate agreed tribal hunting territories. In fact, that’s how the Louisiana city of Baton Rouge got its name; French traders named it to denote “red stick,” referring to the amber color of these juniper poles.

Steam distilled cedarwood oil contains a wide variety of terpenes, including Cedrol, alpha-Cedrene, and Limonene. These terpenes contribute to the botanical’s distinct woodsy scent. At AMASS, we use cedarwood in our Pseudo Citrine, Forest Bath, and Art of Staying In scents, where it lends a warm, cozy aroma.

Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla or Chamaemelum nobile) is a flowering plant in the Asteraceae family native to southern and eastern Europe. Its sweet scent, soft, floral taste, and mild sedative properties make it well-suited for tea time or happy hour.

The word chamomile comes from the Greek words χαμαίμηλον (khamaimēlon) meaning earth apple and χαμαί (khamai) meaning on the ground. Similar in appearance to daisies, chamomile flowers can facilitate the growth and health of surrounding plants. When consumed, often in the form of tea, chamomile flowers are known to reduce anxiety and act as mild sedatives due to the presence of two active ingredients: chrysin and apigenin, a component often found in alcohol. Before hops were introduced, chamomile was often used to flavor beer, and today is used by some craft breweries as a unique flavoring agent.

While there are a number of plants in the chamomile family, Roman and German chamomile are the most commonly used varieties. Despite being different species, the two types of chamomile are remarkably similar in both effect and appearance. Their differences lie instead in their growing patterns and taste; Roman chamomile is perennial and distinctly bitter, while German chamomile grows annually and has a pleasant, sweet flavor. Roman chamomile was given its name not because it is native to the city, but because an English botanist first discovered the species growing in the Coliseum while vacationing in Italy. He brought the bright bud back to England, where it is now cultivated widely.

In Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, a definitive guide to herbal medicine dating back to 1653, English botanist Nicholas Culpeper describes chamomile’s uses in excruciating detail:

“The bathing with a decoction of camomile taketh away weariness, easeth pains to what part of the body soever they be applied. It comforteth the sinews that are overstrained, mollifieth all swellings: It moderately comforteth all parts that have need of warmth, digesteth and dissolveth whatsoever hath need thereof, by a wonderful speedy property.”

Culpeper’s passage on chamomile goes on and on, showcasing the botanical as a true panacea known to soothe any and all ailments. Throughout literature, chamomile is held up as a symbol of youth, with references spanning from Shakespeare to The Tale of Peter Rabbit. In Henry IV, Shakespeare writes, “For though the camomile, the more it is trodden on the faster it grows, so youth, the more it is wasted, the sooner it wears.”

As much as Culpeper and Shakespeare would like to think of chamomile as the botanical equivalent of the fountain of youth, we love it not for its time-bending properties but for its taste. One of the three botanicals in AMASS Botanic Vodka, chamomile offers a soft, floral flavor that plays nice with bright lemon and marigold blooms.

Found in: AMASS Botanic Vodka

Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) is a botanical in the Cinnamomum family native to India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. Commonly confused with its botanical cousin, cassia, cinnamon comes from the inner bark of several tree species and has long been celebrated for its sweetness.

Since the beginning of time, there has been cinnamon. Records show the botanical was imported to Egypt as early as 2000 BCE, where it was used to embalm mummies. The prized spice was considered a gift fit for monarchs and deities, and evidence points it was even gifted to the temple of Apollo at Miletus.

Herodotus and Aristotle wrote of “cinnamon birds” that collected cinnamon sticks from an unknown land and used them to construct their nests, while Pliny the Elder said that cinnamon had been brought around the Arabian peninsula on “rafts without rudders or sails or oars.”

The aromatic botanical was burned in funeral rites and rituals, and though it was far too expensive to be used frequently in funeral pyres in Rome, in 65 AD Emperor Nero purportedly burned a year’s worth of the city’s cinnamon supply at the funeral for his wife, Poppaeae Sabina.

Through the Middle Ages, the spice remained shrouded in mystery, its sourcing whereabouts unknown to the majority of the Western world. When the Sieur de Joinville accompanied Louis IX to Egypt in 1248, he believed that cinnamon was fished up in nets at the end edge of the world – what we now know as Ethiopia.

Eventually the mystique surrounding the plant dissipated, and cinnamon became a common culinary spice, used in Persian, Portugese, and Turkish cuisine for both sweet and savory dishes. In early Modern English, the names canel and canella were used interchangeably with cinnamon, and were derived from the Latin word cannella meaning “tube” for the way cinnamon bark curls up as it dries. These cinnamon sticks are used to flavor everything from rice to mulled wine, while powdered cinnamon is often sprinkled on top of desserts.

Though most commercially produced cinnamon available for purchase today is actually cassia, Cinnamomum verum, or “true cinnamon,” is still prized for its distinctively sweet flavor and aroma.

In AMASS Four Thieves, cinnamon lends a warm, comforting scent that pairs well with other baking spices like allspice and clove.

Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum) are flower buds in the Myrtaceae family native to the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. Woody, spicy, and warm, cloves contain the compound eugenol, which is known for its antibacterial effects.

When the clove forests were first discovered in Indonesia, locals were enchanted with the fragrance and beauty of the plant, which they said "must always see the sea" in order to thrive. The clove tree is an evergreen that grows up to 40 feet tall, with large leaves and red flowers. Its flower buds – what we know as cloves – start out with a pale hue, gradually turning green until they transform into a vibrant red when they’re ready for harvest. To natives of the Maluku Islands, these trees are like family; for each child born, a clove tree is planted under the belief that the fate of the tree is linked to the fate of that child.

Experts believe the oldest clove tree in the world – named Afo – is on the island of Ternate, where it was planted nearly 400 years ago. When the Dutch set fire to the Maluku Islands’ clove trees in an attempt to create scarcity and drive up prices in the 17th century, the natives revolted in a battle. It wasn’t until the French smuggled cloves from the East Indies in the 18th century that the Dutch monopoly was broken, and cloves were brought back to their native soil.

Named after the French word clou meaning nail, clove buds are similar in appearance to nails with their bulbous point and short stem. In Indonesia, the spice is used in a type of cigarette called kretek. While clove cigarettes were banned in the US in 2009 along with most other flavored cigarettes, they are still frequently used in cigars.

The first reference to cloves in literature comes from the Han period in China, in which the spice is listed under the name “chicken-tongue spice.” As early as 200 BCE, those wishing to approach the emperor had to first chew a few cloves to sweeten their breath.

Cloves’ sweet, spicy taste and scent are well-suited for teas and desserts, and they are often lumped into ingredient lists with cinnamon and allspice. Like those other warming spices, cloves contain the compound eugenol, which is known for its antibacterial effects and use as an effective local anesthetic.

Cloves were an important ingredient in the age-old Four Thieves recipe, a concoction of vinegar, herbs, and spices believed to prevent the spread of the plague in medieval Europe. Bands of thieves anointed themselves with the sweet-smelling tincture as they robbed the dead, and cloves, with their strong scent and antibacterial properties, helped mask the unpleasant aromas of the time. In a modern reimagination of the historic botanical blend, AMASS’ Four Thieves line combines cloves, cinnamon, eucalyptus, and allspice for a scent that comforts and soothes. In AMASS Dry Gin, small amounts of cloves are used to impart a woody, spicy flavor.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin and Four Thieves Botanic Hand Sanitizer

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) is an annual herb in the Apiaceae family native to regions spanning from Southern Europe and Northern Africa to Southwestern Asia. One of the oldest known spices, coriander was once considered an aphrodisiac and was often added to love potions.

The word coriander comes from the Greek word koris, meaning stink bug. Thankfully not indicative of the botanical’s taste, the name was given because of the odor coriander plants give off when bruised. While the botanical’s seeds have a warm, nutty flavor, its stems and leaves, otherwise known as cilantro, can taste like citrus or soap, depending on whether or not you possess the OR6A2 receptor gene.

Most coriander today is produced in Morocco, Romania, and Egypt, with small quantities of the plant produced in China and India. A tender herb growing to be only 20 inches tall, the coriander plant produces small, white-pink flowers that are borne in umbel clusters. Its leaves – known as cilantro – are frequently used in Mexican and South Asian cuisine to lend a light, citrusy taste, while its roots offer a much stronger flavor to be used in Thai soups and curries. Coriander seeds, with their herbal nuttiness, are often added to garam masala, and are used to flavor everything from sausages to Belgian wheats to pickled vegetables.

Outside of its culinary uses, coriander is used frequently in tonics and cough medicines. Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, recommended the use of coriander as a medicine, used to treat everything from digestive ailments to joint pain. In the Bible, coriander is mentioned in reference to manna, a food miraculously given to the Israelites during their travels in the desert. The passage simply reads, “Like a coriander seed, white.” The passage says little of the spice’s significance, other than its prevalence during Biblical times. Coriander seeds have been found in ruins dating back to 5000 BCE, cementing it as one of the oldest known spices.

During the Medieval and Renaissance periods, coriander was thought to be an aphrodisiac and was often added to love potions and wine to increase desire and stimulate passion. It is famous for its mention in Arabian Nights, where it was used in a tincture to cure a merchant of impotence.

In gin, coriander is one of the staple botanicals, falling second only to juniper. The two ingredients complement each other so well because they both contain alpha-pinene, a terpene that gives off a fresh, piney taste.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Cubeb (Piper cubeba) is a tropical shrub in the Piperaceae family native to Java and Sumatra. Used as a substitute to black pepper, cubeb has a bitter, spicy flavor reminiscent of a cross between black pepper and allspice.

Nicknamed the “tail pepper,” cubeb was once widely used as a substitute to black pepper. That was prior to 1640, when the King of Portugal prohibited the sale of cubeb to promote the now ubiquitous spice found next to our salt shakers. The botanical is now primarily used as a flavoring agent for gin and cigarettes, as well as in Indonesian cuisine.

Ironically, cubeb cigarettes were sold in the Victorian era as an asthma treatment. Edgar Rice Burroughs, the writer of Tarzan, claims that the story may not have existed if it weren’t for cubeb cigarettes, which he smoked religiously while writing. The brand du jour was Marshall’s Prepared Cubeb Cigarettes, which was so successful it stuck around through World War II.

Cubeb pepper possesses sabinene, a compound known to have antibacterial properties helpful in fighting against bacteria that cause foodborne illness. Lauded as a cure-all in the Tang Dynasty in China, cubeb was administered by Tang physicians to restore appetite, cure demon vapors, darken the hair, and perfume the body. There is no evidence from that time showing that cubeb was used in culinary pursuits, though it was prized as a seasoning for meats and sauces in Europe during the Middle Ages.

A 14th-century morality tale about the dangers of gluttony written by Franciscan writer Francesc Eiximenis describes the eating habits of a cleric who consumed a concoction of egg yolks, cinnamon, and cubeb after his bath, likely as an aphrodisiac. In the 17th century, the Catholic priest Ludovico Maria Sinistrari wrote about methods of exorcism and listed cubeb as an ingredient to ward off incubus, a demon believed to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women. Today, Sinistrari’s formula is quoted by neopagan authors who claim that cubeb can be used in love sachets and spells.

While cubeb’s efficacy as a love potion is questionable, it is without a doubt delicious in gin. The spice contains high levels of limonene, which should give off a strong citrus flavor, although the taste goes largely undetected. Instead, the botanical offers a complex floral hint and peppery finish that mixes and melds well with the other core gin botanicals like juniper and coriander.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) is a genus of over seven hundred species of flowering trees in the Myrtaceae family native to Australia. Steam-distilled eucalyptus oil is a natural deodorizer and antiseptic, and has a piney, camphoraceous scent with a touch of honey that is known to soothe.

Of the over 700 varieties of eucalyptus that abound, most are native to Australia. Every state and territory within the country has its own representative species, and nearly three-quarters of Australian forests are comprised of eucalypts. This wasn’t always the case, however; the oldest eucalyptus fossils are from South America, where eucalypts no longer grow naturally. Despite their current prominence in the Australian landscape, the fossil record of eucalypts is actually quite scarce through the Cenozoic Era, suggesting that the plant’s rise is a somewhat recent development. The oldest known eucalyptus fossil is a 21-million-year-old tree stump found in New South Wales.

While the fossil record of eucalyptus dates back many millenia, it wasn’t until until 1770 when the plant was added to botanical collections. French botanist Charles Louis L'Héritier coined the name eucalyptus in 1777, combining the Greek roots eu and calyptos, meaning “well” and “covered” in reference to the operculum, a cap-like structure that protects the developing flowers. It was luck and happenstance that L'Héritier chose a defining feature of all eucalypts when deciding on a name.

Today, eucalypts are impressive for their resilience. Eucalyptus oil is highly flammable, and in some instances ignited plants have been known to explode. Since wildfires run rampant across their nativelands of Australia, many eucalypt species have adapted to fire, resprouting from the ashes.

Those same oils that make eucalypts susceptible to raging bush fires are also what make the plant so valuable. Eucalyptus plants are prized for their leaves, which are harvested and processed to be used for their essential oils. Of the hundreds of varieties, the most commonly harvest type of eucalyptus is the Eucalyptus globulus, as its leaves contain 70 percent oil.

That oil is steam distilled and used in a variety of products, from toothpaste to deodorant to decongestants. Aromatherapists widely use eucalyptus oil for both its soothing scent and extensive range of health benefits including being anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antiseptic.

The plants usages don’t end their, though; eucalypt wood is commonly used in the production of didgeridoos, a tradition Aboriginal wind instrument in which the trunk of the eucalyptus tree is hollowed out by termites and then cut into the appropriate size and shape. The wood is also commonly used in papermaking, as eucalyptus’ short fibers lend themself to soft, thin materials like tissue paper.

In AMASS Four Thieves and Forest Bath, eucalyptus lends a fresh forest aroma dotted with notes of warm honey and mint.

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) is a flowering, perennial herb in the Apiaceae family native to southern Europe that is used in its entirety; fennel seeds, stems, and leaves all have a wide array of uses in the kitchen.

Indigenous to the shores of the Mediterranean, fennel is now naturalized in northern Europe, Australia, and North America, where it thrives in dry soil near the sea and along riverbanks. It is cultivated around the world, with most commercial fennel seed sold in the US coming from Egypt. All of the aerial portions of the plant are edible; its large leafstalk bases are eaten as a vegetable, while its seeds are often added to breads, Italian sausages, and sauerkraut.

Pliny, the Roman author of The Naturalis Historie, believed that serpents ate and rubbed against fennel after shedding their skins because it improved their eyesight. In the 1842 poem “The Goblet of Life,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow refers to the plant’s ability to strengthen vision: “Above the lower plants it towers, | The Fennel with its yellow flowers; | And in an earlier age than ours | Was gifted with the wondrous powers | Lost vision to restore.”

Conversely, in ancient China, fennel was considered a powerful snake bite remedy. The plant was often hung over doorways in Medieval times to ward off evil spirits, and was believed to be especially effective at the summer solstice.

On ancient Athenian Pheidippides' 150 mile journey to Sparta for the battle of Marathon, he carried along a fennel stalk to invigorate him with courage, as the plant was long thought to give warriors a newfound sense of bravery. The battle itself was reportedly waged on a field of fennel, and because of this, the fennel stalk was held up by the Athenians as a symbol of victory. Charlegmagne too held up the plant, declaring by royal decree that the botanical was essential to every garden because of its purported healing properties.

Prized as both a condiment and an appetite suppressant, fennel seeds were used by the Puritans to make it through Church-mandated fasting days. They brought the tradition with them to the US, where they snacked on seeds in church pews to stave off hunger.

These days, fennel is a common botanical in distillation, used in the preparation of absinthe and aquavit. While milder and more vegetal in flavor, fennel is commonly mistaken for anise in gin. The botanical is found in contemporary gins like AMASS, which have a strong herbal profile.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Grains of Paradise (Aframomum melegueta) are a type of spice in the Zingiberaceae family native to West Africa. Belonging to the same botanical family as ginger and cardamom, grains of paradise have a taste similar to that of black pepper with hints of citrus.

Grown in the swampy habitats of West Africa, grains of paradise were once a major cash crop for the region. Their worth was bolstered by the claims of Medieval spice traders who claimed that the spice could only grow in Eden, which is how it got its name. The Grain Coast of West Africa is named for the spice in the same way the other coasts are named after Ivory or Gold.

Through the Middle Ages and into the early modern period, the theory of the four humors – the idea that the body is governed by the four fluids of blood, yellow bile, phlegm, and black bile – guided the medical practices of the time. In this context, writer John Russell characterized grains of paradise in his book The Boke of Nurture as “hot and moist.”

Roman author Pliny the Elder, meanwhile, referred to the spice as “African pepper.” Quickly renamed grains of paradise, the botanical became a popular substitute for black pepper in 14th century Europe, and was recommended by the Menagier de Paris to improve wine that’s gone stale. When the grains first arrived in Lisbon in 1460, their arrival was so cataclysmic that the price of pepper on the open market collapsed and many of those who had hoarded the spice at high prices were left in financial ruin.

The spice has environmental impacts, as well; research has shown that the presence of the seeds in the diets of lowland gorillas has a beneficial effect on their overall cardiovascular health. The primates feast on the seeds and leaves alike, and the absence of the plant is felt in zoos where captive lowland gorillas often have poor cardiovascular health. There’s no evidence pointing to the plant having comparable effects on humans, although grains of paradise are valued in West African folk medicine for their warming and digestive properties. Among the Efik people in Nigeria, the seeds are used for divination and ordeals determining guilt.

So, what does all that have to do with gin? Throughout history, grains of paradise have played a role in the production of alcohol, especially after their popularity in cooking waned and they began to be used to flavor beer. In the mid-19th century, England was importing somewhere between 15,000 and 19,000 pounds of grains of paradise a year. Imports halted to a stop, however, after a parliamentary act forbade the use of grains of paradise in malt liquor and aquavit. Today, use of the spice has resumed, and it is often used in gin distillation as well. The botanical gives AMASS Dry Gin added depth, working in tandem with other peppery spices like cubeb and long pepper to impart the spirit with a distinctive piquancy.

Hibiscus (Hibiscus syriacus) is a flowering plant in the Malvaceae family native to warm temperate, subtropical, and tropical regions throughout the world. There are several hundred known species of hibiscus, and their culinary significance can be felt across cultures.

In the collective imagination, hibiscus is closely tied to Hawaii. The state’s flower, yellow hibiscus has long been worn by Hawaiian girls as a marker of their relationship status: placed behind the left ear and the woman is married, behind the right and she is single. The beautiful buds are not only used to signify singlehood, however. The striking appearance of hibiscus flowers makes them a popular plant in landscaping, used to attract butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds alike.

The colorful plant is often cultivated for its fibers, which are used extensively in papermaking as well as in the production of rope and canoe floats. In the Philippines, children sometimes use hibiscus to make bubbles. The flowers and leaves are crushed until the sticky juices run out, and hollow papaya stalks are dipped and used as straws to blow bubbles.

The flower’s creative uses don’t stop there. Hibiscus extracts and leaves can help alleviate a dry scalp, and with the addition of some water, a grinder, and a little elbow grease, you can make your own DIY hibiscus shampoo. A more common usage for the plant is as a tea, which is enjoyed across cultures in the form of agua de jamaica in Mexico and bissap in West Africa. Served both hot and cold, hibiscus tea is beloved for its tart, refreshing flavor.

Throughout India, the red hibiscus appears frequently in artistic depictions of the Hindu goddess Kali, often with the goddess and the flower merging in form. Hibiscus as we know it today is the result of hybridization over the course of several centuries and across regions, which is why it’s no surprise that we see the botanical hold such a significant role in cuisines and cultures around the world. Unlike other flowers that add a delicate sweetness to drinks and dishes, hibiscus imbues a bright, vibrant tartness to everything it touches.

Found in: AMASS Dry Gin

Juniper (Juniperus communis) is the defining botanical in gin. In fact, the word gin itself is short for the Dutch word jenever, meaning juniper. A member of the Cupressaceae family, juniper berries give the spirit its signature piney, citrusy taste; essentially, they make gin taste like gin.

Juniper berries are to gin what grapes are to wine; you can’t make the spirit without them. And lucky for gin nerds like ourselves, species of juniper trees abound. Throughout the Northern Hemisphere, there are over 50 varieties of junipers. These coniferous trees typically grow to a height of six to 25 feet, and can be found in the mountains of Central America, tropical Africa, and eastern Tibet, among other places.

The highest known juniper forest in the world is in the northern Himalayas of Tibet at an altitude of 16,000 feet. Remarkably wind resistant, tall varieties of juniper are often planted in rows as windbreaks. These hardy trees, once harvested, serve a variety of functions; the red cedar juniper is used in drawers and closets, and was a common building material in the nineteenth century because of its ability to repel harmful insects like bed bugs. Other varieties, meanwhile, are favored for their berries, which are steam distilled into essential oils and used to fight arthritis, cramps, and other ailments.

The Greeks famously believed that juniper increased stamina, and therefore made a habit of eating the berries before races for a boost. Other remedial uses of the botanical include the use of juniper as a rudimentary form of birth control. The botanical was used to abort unwanted pregnancies in the Middle Ages, with the phrase “give birth under the savin tree” serving as a euphemism for juniper-induced miscarriage.

In the Bible, juniper was often used as a symbol of protection; in one biblical story, an infant Jesus was hidden from soldiers by a juniper tree. Other ancient tales say juniper wood, with its highly aromatic smoke, was used in the ritual purification of temples. To this day juniper smoke plays an important role in the occult, as it is thought to aid clairvoyance and stimulate contact with the Otherworld at the beginning of the Celtic year.

While it’s now well-loved by witchy types, juniper smoke was once used in central Europe to cast out witchcraft. Similarly, the piney fumes were used during outbreaks of the plague, as it was believed that the disease could be dispelled by fumigating the house with juniper smoke while its occupants were inside.

For our intents and purposes though, we know and love the botanical berry for the essential role it plays in gin. In fact, the spirit is named for the plant, as the word “gin” is short for the Dutch word jenever, meaning juniper. If you’ve ever heard gin described as tasting like a “Christmas tree,” that’s all because of our friend juniper.

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) is a root in the Fabaceae family native to the Middle East, southern Europe, and parts of Asia, such as India and Nepal. It is 50 to 100 times sweeter than sucrose, and has long been used as a powerful sweetening agent in gin.

The word licorice comes from the Greek word γλυκύρριζα (glukurrhiza), meaning "sweet root.” And that’s exactly what it is – a sweet root that grows deep in the dirt of well-drained soils in deep valleys with full sun. It has long been lauded for its medicinal properties, used in traditional Chinese medicine to “harmonize” ingredients in a formula. In Ayurveda, it’s used to treat a whole host of diseases, and was long used in Europe as cough medicine because of its anti-inflammatory effects.

In The Divine Farmer’s Herb-Root Classic, Emperor Shennong ordered that licorice be listed as a magic plant that rejuvenated aging men. That was in 2300 BCE. In the time between then and now, the botanical has featured prominently throughout history.

The Egyptians made a sweet drink using licorice root called “Mai sus,” which they believed to be a cure-all for an array of afflictions. The bitter botanical was found bundled in King Tut’s tomb, as to be buried with the plant meant one could enjoy a sweet drink in the next world. Later, Roman and Greek soldiers chewed on licorice to quench their thirst and enhance their stamina. Napoleon Bonaparte was said to be a fan, and to have chewed on the root habitually.

Fast forward to the 19th century, when the botanical got a bit of a rebrand and began to be sold and marketed as a candy. This wasn’t anything new though, really: some evidence shows usage of licorice as a candy dating back to as early as the 13th century. It makes sense–licorice is 50 to 100 times sweeter than sucrose, and its sugary sweetness is detectable in water even when diluted to 1 part licorice candy to 20,000 parts water.

These days, big name candy brands (you know the ones) use the term licorice to sell candy that doesn’t really have any licorice in it at all. Instead, these mass-marketed treats are laden with artificial strawberry and cherry flavors that don’t taste a thing like the bitter anise flavor of licorice.

A common sweetening agent in gin, licorice is used in AMASS Dry Gin both for its distinctive flavor as well as for its ability to alter texture and mouthfeel.

Found in: AMASS Dry GIn

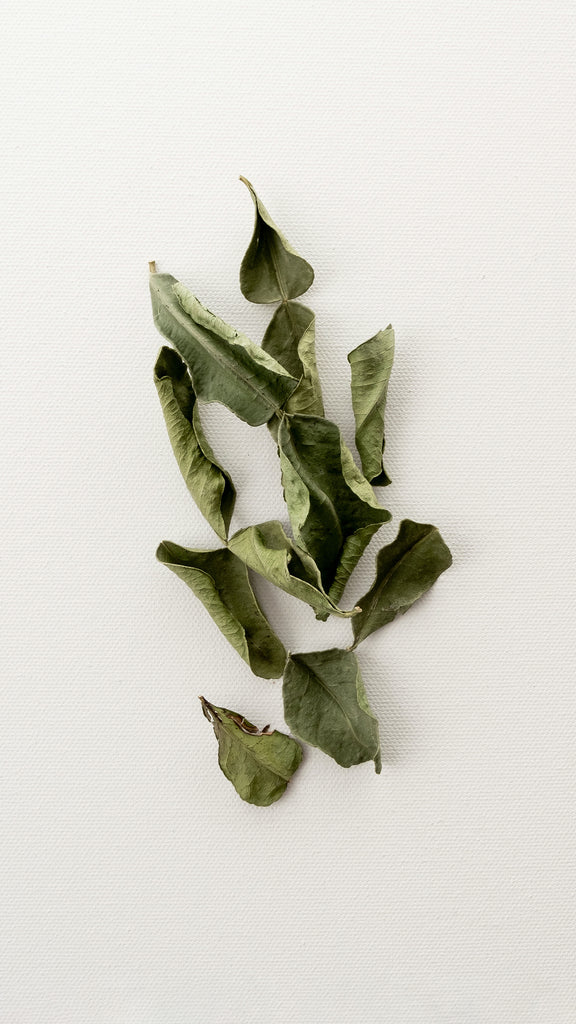

Makrut Lime (Citrus hystrix) is a citrus fruit in the Rutaceae family native to tropical Southeast Asia and southern China. While the fruit itself has an inedibly bitter taste, its leaves when crushed emit an intense citrus fragrance and are used to add a deep yet subtle flavor to Thai cuisine.

Lime leaves are frequently used in Thai cooking to add depth and brightness to dishes like Tom Yum and various curries. The botanical features in Vietnamese, Cambodian, Indonesian, and Malaysian cuisine as well, and is used in a similar capacity as bay leaves, simmering in curries and soups to lend a deep citrus flavor. In Cambodia, lustral water mixed with slices of Makrut lime is used in religious ceremonies, while in other parts of the world, its astringent juice is used in shampoos and cleaning products.

Beyond its decidedly bitter taste, the Makrut lime differs from other lime varieties in that it has irregular, bumpy skin and a small size. Its leaves offer the brightness and freshness of citrus fruit, but without the harsh acidity and sharpness that often accompany them, creating a subtle, more mellow flavor.

Makrut lime leaves possess the compound (–)-(S)-citronellal, which accounts for the plant’s characteristic aroma. Other, less significant components like citronellol, nerol, and limonene make up the rest of the rest of the leaves’ composition.

In AMASS Dry Gin, the lime leaf acts as a bridge between bright citrus and botanicals like juniper that possess a slightly medicinal quality.

Lion’s Mane Mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) is a type of fungus in the Hericaceae family native to North America, Europe, and Asia. Long lauded as a cure-all in Chinese medicine, the botanical possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and is purported to stimulate and enhance nerve cells.

First found in North America, the lion’s mane mushroom likes to grow on hardwood trees and decaying logs. It’s found most commonly during the late summer and fall months, when it thrives in the fallen autumnal leaves. This fun fungus goes by quite a few peculiar nicknames, including but not limited to: the monkey head mushroom, bearded tooth mushroom, satyr's beard, bearded hedgehog mushroom, pom pom mushroom, or bearded tooth fungus.

Like ashwagandha and Reishi mushroom, lion’s mane is classified as both a nootropic and adaptogen, meaning it helps the body cope with stress and enhances cognitive function. Long lauded as a cure-all in Chinese medicine, lion’s mane mushrooms’ health benefits have only recently been accepted in Western medicine. Research says that lion’s mane mushrooms contain medicinal substances responsible for reducing blood sugar and regulating lipid levels. The botanical possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and is known to stimulate and enhance nerve cells. In the future, lion’s mane could even help treat and prevent cognitive illnesses like Alzheimers and Parkinsons.

TL;DR: a healthy dose of this mighty little mushroom does the body (and mind) a whole lot of good.

For us, flavor always comes first though, which is why we love lion’s mane in our gin. The plant’s culinary applications don’t stop at spirits, though; if eaten when young, the mushroom’s texture is akin to crab meat. Historically, lion’s man was reserved for royalty because of its similar taste to seafood. While it’s more commonly found in capsule or tablet form at your local health foods store, some specialty grocers and fungus purveyors will offer the delightful delicacy. Be careful, though; lion’s mane can be bitter if not cooked until crispy along the edges. Caramelizing it in olive oil or butter until crisp is the best way to go when cooking it at home.

While an uncommon feature in gin, lion’s mane gives the spirit a distinctive earthy finish with a kick of umami.

Long pepper (Piper longum) is a spice in the Piperaceae family native to India. As its name suggests, it is long and conical in shape with tiny, tightly-clustered peppercorns. It has a taste similar to, but hotter and slightly more complex than that of black, green, and white pepper.

The oldest known reference to long pepper comes from the ancient Indian textbooks of Ayurveda, where it was listed as a powerful medicament. One modern remedy based on Ayurvedic tradition calls for a mixture of long pepper, ghee, sesame oil, and milk, a concoction believed to enhance libido, aid sleep, and prevent colds.

In the fifth century, the botanical reached Greece, where it became a significant, well-known culinary spice, comparable in usage to black pepper. In fact, the two spices were often confused with each other, until Theophrastus distinguished black and long pepper in the first work of botany.

The word pepper is derived from the word for long pepper, pippali, a fact that furthered confusion between the two spices. A powerful medicine and flavoring agent, long pepper was so valuable throughout the Middle Ages that tenants were known to have paid their landlords with it.

Nearly ten centuries after the botanical made its way West, the discovery of the chili pepper in South America led to the decline in popularity of the long pepper, as dried chili pepper was remarkably similar in taste but could be grown just about anywhere. Tedious and labor-intensive, harvesting long pepper was no longer worth the effort, and so it faded out of popularity.

Today, long pepper is rare and difficult to find in the West, though it is still popular in Indian, Pakistani, Indonesian, and Malaysian cooking. It’s used in dishes like Nihari, a beef or lamb stew popular in Pakistan, as well as to lend a sharp piquancy to Nepalese vegetable pickles. Labelled as pippali, it can be found at most Indian grocery stores.

In AMASS Dry Gin, long pepper joins cubeb and grains of paradise for a peppery finish on the rear palate.

Marigold (Tagetes patula) is a flower in the Asteraceae family native to the south of Mexico, though now naturalized around the world. The genus name of the botanical – Tagetes – comes from the Etruscan prophet Tages, born from the plowing of the earth. The name likely refers to the ease with which marigolds come out each year.

Believed to hold both medicinal and magical properties, marigolds were long held as a panacea, used to treat hiccups, save victims of lightning strikes, and allow weary travelers to cross bodies of water safely.

The English word marigold is derived from Mary’s gold, and the flower holds cultural significance around the world. In pre-Hispanic Mexico, marigolds were considered the flower of the dead, and today are still used widely in Day of the Dead celebrations. Their blossoms are used to decorate households and altars and are often scattered on relatives’ graves, which is why marigolds often grow in abundance in cemeteries.

In Hindu religious ceremonies, marigolds are strung up as garlands to decorate during the harvest festival, as they are the same hue as the maize and peppers that also feature prominently in festivities. They’re a remarkably durable plant, as is evidenced by the fact that they journeyed across the Atlantic twice, travelling 3,000 miles north of their origin point.

A natural deterrent to several common insects, as well as nematodes, marigolds are often a companion plant to the tomato, eggplant, chili pepper, tobacco, and potato. Because of their vibrant orange hue, they’re often cultivated for their dye, and in some cultures are used as a culinary herb in a similar capacity to tarragon. While some varieties are bred to be scentless, the common marigold has a distinct musky, pungent aroma.

In South Africa, marigolds are a useful pioneer plant, a hardy species that is the first to colonize barren environments that have been disrupted and destroyed, often by fire.

In vodka, marigold acts as a natural substitute to glycerine, creating a smooth and full mouthfeel that mixes and melds with the bright floral notes of chamomile and lemon zest.

Found in: AMASS Botanic Vodka

Mint (Mentha × piperita) is a plant in the Lamiaceae family distributed across Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and North America. Its distinctly cool and fresh taste makes it a common culinary herb, used in classic cocktails like the mojito or the mint julep.

Around the world, there are nearly two dozen species of mint. Due to the plant’s propensity to spread wildly, some varieties of mint are considered invasive, thriving and eventually dominating wet environments with damp soil. Mint is not a pest, though; the fruits of its labor are beloved across cultures. In Middle Eastern cuisine, the herb is paired with lamb, while northern African and Arab countries enjoy Touareg tea, a popular beverage steeped with spearmint leaves and sugar.

Mint is also frequently used as a breath freshener, used to flavor toothpastes and chewing gum for a squeaky-clean taste. Historically, the herb was used to treat stomach aches, and it’s still remarkably effective for that use; sipping on peppermint tea is known to soothe an upset stomach. The ancient Greeks rubbed mint leaves on their arms, believing the astringent herb would make them stronger, bigger, faster. It didn’t necessarily work, but the smell of the plant does have the ability to instill a sense of vigor.

In fact, in Greek mythology, mint was considered the herb of hospitality, used as one of the first known room deodorizers. Its leaves were strewn across the floor so that every time someone stepped on the herb, its refreshing aroma would emanate through the room. This was to cover the stench of soil from the ground, as well as the other less-than-sweet smells of the time.

As we mentioned, varieties of the herb abound, but usually when we say “mint leaves,” we’re talking about the classic spearmint variety. In John Gerard’s 1597 book Herbal, he wrote of spearmint, "It is good against watering eyes and all manner of break outs on the head and sores.” He also touches on the emotional benefits of the botanical, saying, “the smell rejoice the heart of man,” and for that reason it ought to be strewn about places of “recreation, pleasure and repose.”

At AMASS, we use mint in Riverine to give it the sharp, refreshing finish expected in a sophisticated spirit, as well as a touch of sweetness. In Basilisk Breath, mint blends with sweet basil and other aromatic herbs to deliver a refreshing and invigorating scent.

Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) is a spice in the Myristicaceae family native to the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. Its warm, nutty flavor and scent make it a common companion ingredient to cinnamon and allspice.

The nutmeg we know and love is just one part – the seed – of the Myristica fragrans tree, a dark-leaved evergreen that grows in warm-weather environments like Penang Island in Malaysia and the Maluku islands of Indonesia, as well as on islands dotting the Caribbean.

The outermost layer of the nutmeg seed is known as mace, which has a flavor similar to but more delicate than that of nutmeg. Both spices are used frequently in cooking and baking, appearing in dishes like oxtail soup in Indonesia, jerk chicken in Jamaica, mulled wine and eggnog in regions across Europe and North America, and Caribbean cocktails like the Painkiller and Barbados rum punch. Nutmeg essential oil is also increasingly popular, used in both culinary and olfactory pursuits.

The English word nutmeg comes from the Latin word nux, meaning nut, and muscat, meaning musky. While the spice doesn’t quite count as a legume, it most likely gets its name from the nutty aroma and flavor it adds to everything from stews to sweets. In fact, in the 12th century, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI had the streets of Rome fumigated with nutmeg to ensure a sweet-smelling environment for his coronation.

There is evidence pointing to the discovery of both nutmeg and mace as early as the first century AD, when Roman author Pliny the Elder wrote of a tree “bearing nuts with two flavors.” In addition to the plant’s unique flavor properties, nutmeg was prized by the social elite as a powerful hallucinogenic. While the spice produces no neurological response when consumed in small doses, if ingested raw or in oil form in large amounts, the botanical does have some serious psychoactive effects, not all of which are fun; nausea, dehydration, and palpitations are all on the laundry list of adverse effects from hitting the nog too hard.

Like clove, another spice native to the Maluku Islands, for a time nutmeg production in the East Indies was largely controlled by the Dutch. The Dutch had waged a bloody war to control nutmeg production, and took large quantities of the spice back to Holland to store it in a warehouse, often burning the plant to keep prices artificially high. It wasn’t until negotiations over the Island of Manhattan were made that the Dutch traded what is now New York City for control over a nutmeg-producing island owned by the British.

Despite the spice’s storied, sometimes troubled past, we love it today for its sweet, warm taste. When distilled, nutmeg gives AMASS Dry Gin a necessary subtle heat and lingering warmth on the palate.

Orris (Rhizoma iridis), a member of the Iridaceae family commonly called 'Queen Elizabeth Root,’ is the root of the flower iris (Iris germanica and Iris pallida) which grows primarily in rocky regions of the Mediterranean.

On its own, dried orris root smells like violets. But when combined with other botanicals, its power is multiplied. In perfumery, the root is beloved for its ability to bind to and enhance other spirits. It makes other ingredients, like vetiver and mandarin, smell more like themselves, and helps deliver a cohesive, balanced aroma. You know it best in Chanel No 5, as well as in iris-dominant fragrances by high-end houses like Yves Saint Laurent and Prada.

When distilled into gin, its effects are similar, adding depth and texture to the spirit while delivering a subtly floral, grassy note. To the nose, it's dry and clean, comparable in taste to licorice sticks. And despite its prevalence across spirits and scents brands, the botanical is actually quite labor-intensive to harvest and produce.

The process begins in the fields. Prunetti Farm in the Italian village of San Paulo is a top producer of the plant, and each year a festival is held to celebrate its abundance. After three to four years of growth, the roots of the plant are dug up in August and left to dry for a whopping five years before being ground to a fine powder. That’s a total of ten years from the time it takes the botanical to make its way from the ground to the bottle, but the effort is worth it.

Just as with ginger, turmeric, and galangal, the amount of care taken to peeling and preparing orris root largely impacts its quality. Taking the time to carefully prep the plant ensures prime orris, improving its smell and flavor.

The result is, dare we say, magical, and the botanical has been used for centuries as a key ingredient in all kinds of witchy spells. In Japan, its roots were hung around houses to protect against evil spirits, and in other occultish traditions the plant was used as a love potion, its powder sprinkled in sheets and in sachets.

Us? Well, we like to use it in gin, where it plays nice with the other 28 botanicals in our spirit and makes their flavors really sing. It also shows up in Riverine, adding complexity and depth to the non-alcoholic spirit.

Patchouli (Pogostemon cablin) is a plant in the Lamiaceae family native to tropical regions of Asia. Its strong, woody scent has long made it a popular botanical both for incense and other forms of perfumery.

A small, perennial herb, patchouli grows in warm climates throughout Asia, stretching from Cambodia to Taiwan to the Philippines. It thrives in hot, humid weather, and though the plant is quick to wither and dry out when it’s low on water, a quick shower will bring it back to life easily.

While the patchouli plant is now extensively cultivated across countries, Indonesia remains the top supplier, producing nearly 90% of the global volume of patchouli oil year after year.

Despite its somewhat musty scent, the patchouli plant is actually quite verdant. In fact, the word patchouli comes from the Tamil patchai, meaning green leaf. In addition to its grassy foliage, the plant also bears small, pale-pink flowers. These buds are not very fragrant, however; its the patchouli’s leaves and stems that are reserved to be steam distilled into essential oil.

These leaves and stems can be harvested several times a year, though opinions differ on the best time to extract their oil. Some say fresh is best, while others argue that boiling the dried leaves and then fermenting them leads to the most potent, high quality oil.

This oil is an important ingredient in incense, which releases fragrant smoke when burned. The ritual of burning incense has a storied past, holding both cultural and religious significance in many parts of the world. In the 60s across the US and Europe, the practice became a part of the counterculture hippie movement, which is why today the scent of patchouli has strong ties to the age of free love.

The plant’s uses don’t stop there. In addition to being a favorite fragrance, patchouli oil is also used to repel pests. It is remarkably effective at keeping away the Forosman subterranean termite, a species of insect native to southern China, Taiwan, Japan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Hawaii, and the continental United States known for consuming wood at a rapid rate.

At AMASS, we use patchouli in Forest Bath to lend a warm, earthy note to the scent.

Reishi Mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum) is a type of fungus in the Ganodermataceae family native to tropical and temperate regions of Asia, as well as in the northern Eastern Hemlock forests of North America. A powerful plant in traditional Chinese medicine, Reishi is known for its therapeutic properties and tonifying effects.

Reishi mushroom is known as “lingzhi” in Chinese, which translates to “mushroom of immortality,” “divine mushroom,” or “magic fungus.” And it is magical – since it was first discovered by Chinese healers more than 2000 years ago in the temperate forest at the base of the Changbai Mountains, it’s been prized for its medicinal properties, as well as for being a token of good luck.

The plant was first featured in the Herbal Classic of Shen Nong, a book from several millennia ago detailing the benefits of various botanicals. In it, the Reishi mushroom is listed for its ability to strengthen cardiac function, enhance vital energy, increase memory capability, and promote anti-aging effects.

In modern-day Japan, Reishi is even listed as a cancer treatment due to its propensity to heal. It wasn’t always so readily available though. In the wild, Reishi mushrooms grow at the base and stumps of deciduous trees like the maple. Only two or three out of 10,000 such trees will have Reishi growth, making it a rather rare commodity. For that reason, for much of its history only the nobility could afford to use the plant.

It was long believed in Chinese mythology that the fungus grew in the homes of the immortals on P’eng-lai, or the Isles of the Blessed, off the coast of China. It remained an exclusive, expensive ingredient, believed to hail from far flung mythical lands until somewhat recently. It wasn’t until the 1980s, when a Japanese man by the name of Shigeaki Mori developed an effective method of cultivating Reishi mushrooms on hardwood logs or wood chips, that the shroom became far more available and affordable.

Here at AMASS, we use the botanical in our Dry Gin, where it lends umami notes and earthy undertones to ground light and bright lemon, grapefruit, and lime leaf.

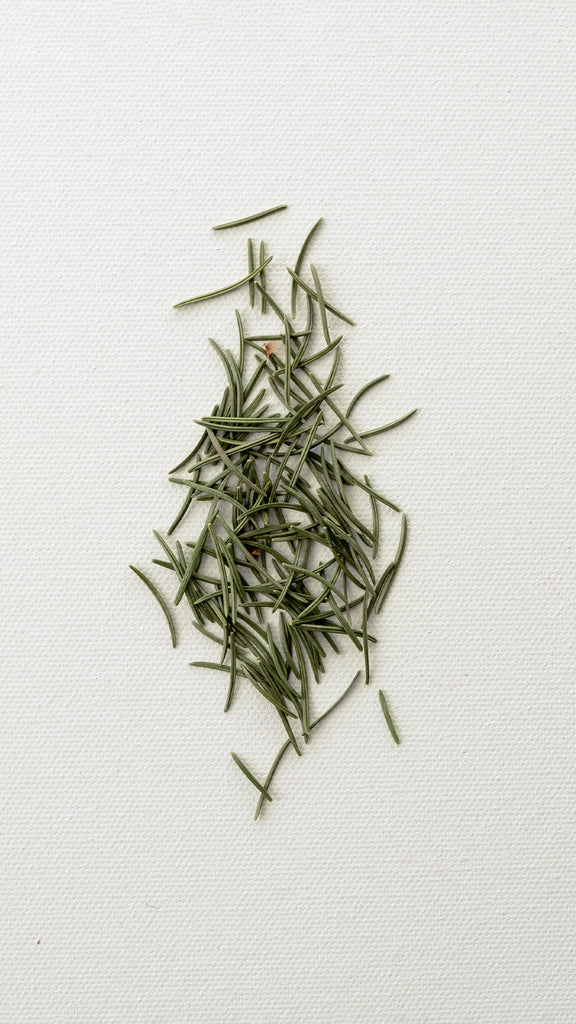

Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) is a woody, perennial herb in the Lamiaceae family native to the Mediterranean region. Sweet and herbal, it’s a common ingredient in food and drink, and is believed to improve both memory and recall.

The word rosemary comes from the Latin phrase os marinus, meaning “dew of the sea.” It’s a romantic enough expression, but is meant quite literally here; the plant thrives in the rocky coastal regions of the Mediterranean. Standard varieties can grow to be three feet tall, although some overachieving varietals grow to stand at a whopping six feet.

Wild rosemary flowers in late spring, when it sprouts buds in seaside shades of white and blue. Its sweet, herbal taste makes it a delicious addition to countless cuisines, though it shows up most often in Mediterranean fare and in herbs de provence. You’ll find it outside the kitchen too in perfumes, incense, candles, shampoo, and even cleaning products. That’s thanks to the fact the rosemary plant contains salicylic acid, the forerunner of aspirin now commonly found in skincare products.

Back in 1987, researchers at Rutgers University in New Jersey patented the food preservative rosmaridiphenol, derived from rosemary and now used in plastic food packaging and cosmetics. Its uses extend past packaged goods though; the herb has long been used to aid in memory. It’s fittingly been used as a symbol of remembrance for the dead, with mourners throwing the herb into graves. It’s because of this time-honored tradition that rosemary grows in abundance on the Gallipoli Peninsula, where many Australians died during WWI.

Sir Thomas Moore was once quoted saying, “As for Rosmarine, I lett it runne all over my garden walls, not onlie because my bees love it, but because it is the herb sacred to remembrance, and, therefore, to friendship; whence a sprig of it hath a dumb language that maketh it the chosen emblem of our funeral wakes and in our burial grounds.”

In ancient Greece, scholars would wear wreaths of rosemary to improve recall while taking exams. The botanical also frequently featured in weddings for the same reason, sometimes even being planted at the wedding venue to help the couple remember their vows. The saying “Where rosemary flourished, the woman ruled,” caused many husbands to uproot the plant.

The herb was also thought to dispel negativity, and was therefore placed under pillows to ward off nightmares. Us? We use the plant in our personal care line, where its extract softens hands and its essential oil lends a fresh, herbaceous aroma. In AMASS Dry Gin and Riverine, the herb lends a lovely sweetness and long finish. Add a sprig to your next cocktail to bring out the flavor even more.

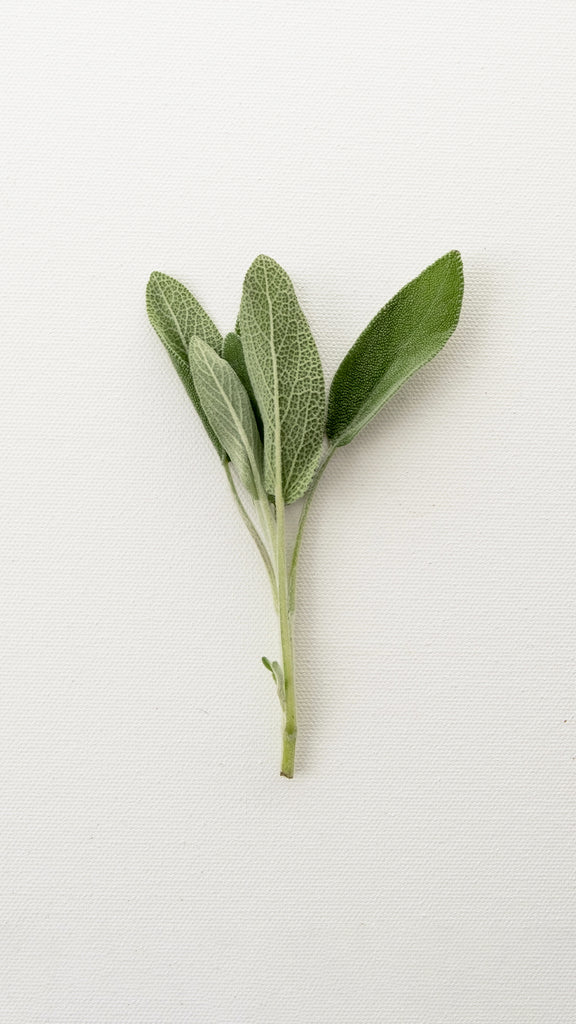

Sage (Salvia officinalis) is a perennial plant in the Lamiaceae family native to the Mediterranean region. Its soothing scent makes it a commonly used plant in aromatherapy.

Since ancient times, sage has been praised as a “holy herb,” used to ward off evil and snakebites and increase fertility. Theophrastus wrote about two different sages – sphakos and elelisphakos – and later Pliny the Elder said the latter was the true sage known as salvia by the Romans. He explained its uses as a diuretic, local anesthetic, and a styptic.

Later in the early Middle Ages, Charlemagne recommended the plant for cultivation, and it grew wildly in the monastery gardens. Its reputation as a powerful plant remained throughout the Middle Ages, with some even calling it S. salvatrix, meaning sage the savior. Le Menagier de Paris recommended it for washing hands at table, and its culinary applications became more widespread, too; sage soup was a favorite of the time.

In John Gerard’s 1597 Herball, he wrote that sage "is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy, and taketh away shakey trembling of the members."

And so it was. Like countless other herbs, sage secured its position as a panacea, used to treat, well, everything. In 1753, Swedish botanist Carl Linneaeus officially listed the herb in his writings, formalizing what was already well-known: sage had the capacity to heal.

Fast forward to today and we know sage for its frequent appearance on our Thanksgiving tables, showing up in sweet potato and stuffing dishes. In France and English, sage sauce is a popular side, while Italians like it best in saltimboca. For centuries now, the British have considered sage an essential herb alongside parsley, rosemary, and thyme, a list of ingredients that inspired Simon and Garfunkel to write an album by the same name in 1966.

Sage essential oil, which contains cineole, borneol, and thujone, is prized for its soothing scent. At AMASS, we use the botanical in our Basilisk Breath and Forest Bath scents to lend a clean, herbaceous aroma.

Sarsaparilla (Smilax ornata) is a tropical plant in the Smilacaceae family native to South America, Jamaica, the Caribbean, Mexico, Honduras, and the West Indies. Its name has become synonymous with a type of soft drink originally made from sarsaparilla root.

Sarsaparilla. Its name conjures images of old timey cowboys sitting in saloons, tossing back pints of beer, yes, but also sarsaparilla, a root beer-esque soft drink made from the root of the Smilax ornata. Truth be told, that’s an accurate image: food writer Ruth Tobias has similarly noted that sarsaparilla evokes ideas of "languid belles and parched cowboys.” She’s right.

In the early days of soft drinks in the 19th century, manufacturers often used health claims to promote their products. Because of this, sarsaparilla, a known immunity booster, was used as a flavoring agent in root beer, often in conjunction with sassafras. Today, while old-fashioned root beers still use the plant, the extract is much less used, replaced with artificial flavorings and a whole lot of sugar.

But sarsaparilla, the plant, has its own history and set of usages aside from sarsaparilla, the drink.

In Spanish, sarsaparilla is known as zarzaparrilla, which is derived from the words zarza meaning bramble, parra meaning vine, and illa meaning small. The plant grows deep in the canopy of the rainforest, its trailing vines and prickly stems feeling at home amidst the lush greenery.

Like many plants of days yore, sarsaparilla was often prized for its medicinal properties, though these were not always accurate. From the 15th to 19th centuries, the most popular use of the plant was for the treatment of syphilis. By the 18th century, its effectiveness as a treatment for venereal diseases was largely debunked, but it took some time for it to become completely retired. However, the botanical continued to be used to treat arthritis, increase libido, and boost the immune system.